If you feel you need to ban technology, you probably need DigCit, instead.

Recently, Susan Dynarski wrote an op-ed in the New York Times about why she bans laptops in her lectures and meetings. Her writing inspired very strong responses on both sides of the issue, and it makes sense. Anyone who has ever tried to teach a room full of students with technology has fought this battle. As an advocate for educational technology seeking a Master’s Degree in this field, I, too, have had fleeting moments where I would love to take all the cellphones and Chromebooks in my classroom and toss them into the bay — especially when my students hack around the filtering sites so they can watch Netflix all day and jam the bandwidth. But is banning technology in a time when technology is so much a part of all of our lives really the most responsible thing to do?

How did we get here? Many of us grew up going to school in a time when computers were nonexistant in school, or relegated to a computer lab in another part of the school or back of the classroom. We did not have access to 24/7 technology for every task we do. Our students, on the other hand, grew up with a gadget in hand from the first minute they could express boredom. Technology has always been part of their lives. If we did successfully ban technology from our classrooms, students would leave school, and before reaching the bus stop, would have their cellphones out, and probably doing several online tasks at the same time without missing a beat. They will probably use their technology for the rest of the evening, and check it first thing after waking up in the morning. They work, play, communicate, and perform monetary transactions online. These students are citizens of a community that didn’t exist a generation ago — a digital community that is the space where many of the transactions that used to take place in physical space now occur. Whether we love technology or hate it, this community is as real as the ones we live and work in every day, but it comes with some unique benefits and deficits, depending on how we exist within it.

When we ban technology, we might get the immediate payoff of students appearing to be more focused in class. But by banning technology in our classrooms, we deprive students of opportunities to learn and practice good digital citizenship, which will equip them to be more responsible users of technology in their adult lives. We are already seeing the consequences of having a generation of students grow up with banned and blocked technology and a lack of training in positive digital citizenship. Plagiarism is on the rise in our society, with scandals affecting everyone from adacemics to news outlets to the White House. Technology-based distraction at work is a huge problem among businesses. Online threats to children’s physical safety are everywhere. Being distracted by technology is so common, it even affects our personal safety. There are so many problems with hacking that I don’t even know how to sum it up into one sentence for the purposes of this blog post. In fact, there are so many problems with the online community that I can’t even begin to list them all here. But that online community is not going away, and as more and more of our daily interactions and business transactions move online, we miss huge opportunities to both equip our students to stay safe and productive with technology, and to contribute to a better online world by being creators of these future online spaces.

When we block and ban technology, we fail to exist with our students in these online spaces and model positive digital citizenship. We don’t prepare students for interacting and working in an online space. We don’t help them work through issues like cyberbullying, trolling, and intellectual dishonesty. We don’t help them learn to balance tech use with mindfulness in the physical world. In fact, we don’t know what threats they face, because we aren’t there with them. Blocking technology for our students when they have access to it at home is like driving to the worst part of town, kicking the kids out of the car, and driving off. It is not only irresponsible to drop the ball with digital citizenship, it sets our students up for real life danger, and it ensures that the future of these online spaces will continue to present the same kinds of dangers to others.

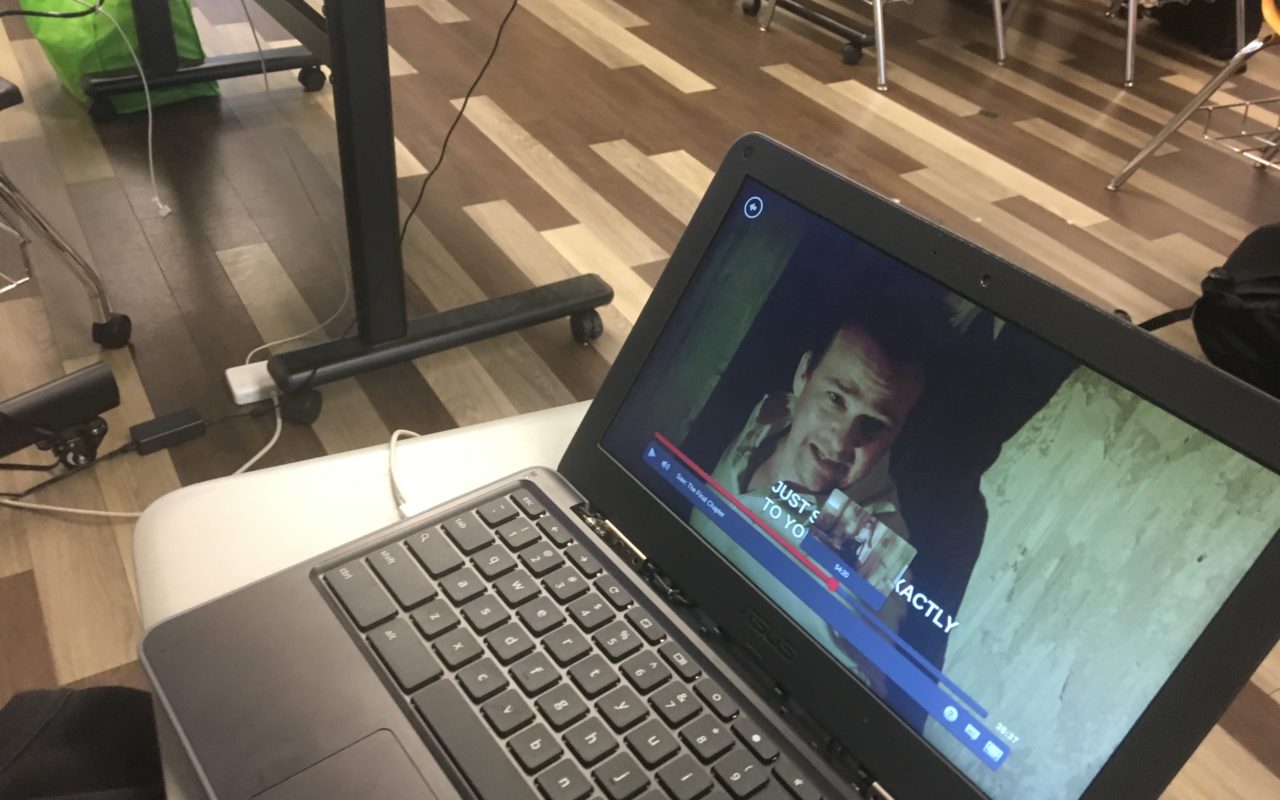

A positive digital citizenship plan with consistent modeling and enforcement is the only good way to handle the frustrations of having technology in the classroom. Though I understand Dynarski’s perspective on the frustrations of digital distraction in the classroom, (that photo at the top of the page is from a student caught watching Netflix in my classroom during instructional time) I also see our common problem as an opportunity to work with students who are exhibiting a lack of good DigCit norms, and who will simply leave our classes and be distracted someplace else. My suggestion to her would be to have an honest discussion with her students about digital citizenship and to create better norms for balancing technology and non-tech learning –– and then to advocate for better DigCit norms at her University, too! This is exactly what I’m doing in my own school.